Portrait of Claude-Adrien Nonnotte by Dorat Nonnotte.

One of Voltaire’s harshest critics in the second half of the eighteenth century was the Jesuit Claude-Adrien Nonnotte, who published a two-volume series bluntly entitled Erreurs de Voltaire (Avignon, 1762). About the Annales de l’Empire, Nonnotte wrote that Voltaire’s readers ‘find within nothing but a boring rhapsody, where he repeats, reiterates and rehashes what he has repeated, reiterated and rehashed in a thousand sections of his other works’ [‘n’y trouvent qu’une rapsodie ennuyeuse, où il répète, redit, rabâché ce qu’il a répété, redit, rabâché dans mille endroits de ses autres ouvrages’] (Les Erreurs de Voltaire, vol.3 (n.p., 1779), p.305, quoted in Œuvres complètes de Voltaire, vol.44A, p.159).

This particular accusation merits some consideration, chiefly because it is partially correct. Whether Voltaire’s rhapsody is boring is a matter of opinion, but there is undeniably a great deal of borrowing of material between the Annales and the Essai sur les mœurs, on which work he had paused in order to write the Annales. Rather than simply lifting blocks of text from one work to the other to speed up the composition process, Voltaire’s self-plagiarism involves the paraphrasing of a longer passage in the Essai into a shorter passage in the Annales. Henri Duranton quotes and analyses specific examples in ‘Annales de l’Empire, Essai sur les mœurs, Histoire du parlement de Paris: trois œuvres pour un fonds commun’ (in Copier/Coller: Ecriture et réécriture chez Voltaire, ed. Olivier Ferret, Gianluigi Goggi and Catherine Volpilhac Auger, Pisa, 2007, p.139-47).

So what? It should come as no surprise that history repeats itself, let alone history books written by the same author on similar subjects. It is only natural that the Annales, a year-by-year account of the history of the Holy Roman Empire should bear some similarity to the chapter on that same empire in the Essai, a work of universal history. Nonnotte is most likely referring to ideological repetition rather than repetition of factual information. As Voltaire’s contemporaries in the Göttingen School of History were keen to highlight, he was not an academic historian (see ‘Voltaire vu par les historiens allemands’, OCV, vol.44A, p.15-28). He explains in La Philosophie de l’histoire (OCV, vol.59) that he is instead a philosophical historian, a discipline that Voltaire appears to have invented for himself in this short work later incorporated into the Essai (see Nicholas Cronk, ‘Conclusion: historien philosophe’, OCV, vol.21, p.259-67).

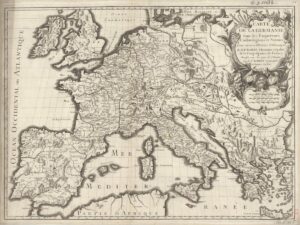

‘Carte de la Germanie sous les empereurs carlovingiens et saxons pour servir à l’histoire d’Allemagne du R. P. Barre’, by Robert de Vaugondy, in Joseph Barre, Histoire générale de l’Allemagne (Paris, 1748).

Philosophical history is concerned with using the past to highlight broader philosophical issues and to extract moral lessons from the events described. Consequently, it ties into Voltaire’s broader philosophical project to promote reason and tolerance while ridiculing fanaticism in all its forms. In this way, Voltaire’s histories are essentially repackaged philosophy, using case studies such as the Holy Roman Empire to help explain the philosophical points made in ostensibly philosophical works such as the Traité sur la tolérance (OCV, vol.56C). The histories endeavoured to make this philosophy more accessible, particularly to young people, by using exciting historical examples to illustrate moral points.

While in this case partly a result of the rapid composition and overlap of sources between the Annales and the Essai, this self-plagiarism is an essential component of Voltaire’s writing process and authorial persona. His work is known for its plurality of voices and genres, but more often than not these different components are all working towards a common goal. The Annales, like so many of the other poems, plays and short stories in Voltaire’s hugely diverse œuvre, insistently puts forward the same philosophical worldview. In this history book we find lessons on the evils of tyranny, the barbarity of fanaticism and the hypocrisy of the Catholic establishment (see chapters on Charlemagne, Otto the Great and Frederick Barbarossa (ch.1, 12 and 22) sketched out in the ‘Gallery of emperors’), all classic Voltairean subject matters that are inventively woven into nearly everything he writes. In this way, we can agree with Nonnotte: Voltaire is nothing if not consistent.